Angela Nishimoto with friend Jonathan Morse, a photographer.

The following is an edited version of an interview that fellow writer Angela Nishimoto conducted with Pat Matsueda. Angela has an interest in editing and publishing and took a class in the latter this past semester at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. In fulfillment of a class assignment, she interviewed Pat on writing, editing, and publishing.

I know that you are a fine poet. When did you first realize that poetry was a genre that was for you? How did that come about?

Poetry is an immense river in which my little craft has floated, explored, been invited places, and been changed. Even though I’ve written poems that I’m proud of—that I want others to read—I would be unhappy if I were to write poetry only. Writers make literary material out of thoughts, feelings, words, and music—music being meaning, significance, depth, power, etc. Sometimes this material comes out as poems, sometimes as prose. So I don’t think of myself as a good poet or someone who has chosen a genre. I’m like a traveler, moving around, trying to get to that place I don’t know yet.

You wrote a novella, Bedeviled. What made you move into prose?

Well, it wasn’t so much a move as a desire to get Ted Koga’s story out in the world. The story is based on real-life incidents. About 20% of it is true and the rest fiction.

Like many of my poems, Bedeviled is about healing and redemption, and I wanted people to read about Koga’s passage from a life of lying and falsehood to acceptance of his mistakes and the reasons he was flawed. I hoped readers might get to know him and ponder his dilemma—to empathize with his efforts to tear apart the conventional notion of morality and to rebuild it from scratch, i.e., from the essential elements of his character. In this effort, I was greatly helped by my publishers, Tom Farber and Frank Stewart, who saw in the story a worthy book and suggested ways to make it better.

The other day I was rereading my old blogposts about Yi-Fu Tuan, the renowned geographer, and Robin Williams and feeling that I should maybe collect these and other posts in a book.

People who read these and Bedeviled may see connections between them. Among the subjects I covered in the posts were feelings of suicide and the terrors of being male.

I've come to visit you in your office several times over the years, and I remember you at your desk, copyediting. It takes a sharp eye and sustained concentration to do that kind of close work, I think. You also have success as a free-lance editor. Please tell me about the ins and outs of that kind of work. I remember that I've seen manuscripts in process, and some of the writing seems to need a guiding hand for the editor bring out the special points of the particular work.

Well, there is a lot to say about the “ins and outs.” For Manoa Journal, I copyedit hundreds of pages of prose and poetry a year, proofread, typeset, work on our website, help with marketing copy, draft grant applications, administer projects, handle email correspondence, and so on. Because the staff is small, such multi-tasking is necessary. Despite my having done most of these things for almost thirty years, I am still learning.

To do our editing and production work, we have come up with detailed procedures. We use desktop publishing software, Excel spreadsheets, and other tools to keep track of dozens of literary works and produce a book-sized issue every six months. As the head of the office, Frank Stewart reviews my editing before it goes to the author. When we disagree, we talk about it until we reach a compromise we can both live with.

In our office, business correspondence is critical to developing trust, forging relationships and agreements, reaching satisfactory compromises, and so on. “Correspondence” sounds dry and limiting, but it draws on precision, self-awareness, confidence, understanding of human nature, diplomacy, discretion, sense of timing, and other qualities. In teaching me how to conduct the business of the journal through correspondence, Frank has been an invaluable mentor.

Let me add that we coordinate our work with the journals department of the University of Hawai’i Press, our publisher, and our designer, Barbara Pope Book Design.

My small editing business is a modest enterprise, founded in 2004. To learn about what I do, I’d recommend reading these pages of my website:

FAQ (This page also has a video I made to explain the production process for a publication such as Manoa Journal.)

In recent years, I was given two projects—Sea Home by Phyllis Young and Everything There Was to Tell by Ben Schwartz—that allowed me to contribute something of value. Happily, my work on Ben’s book prefigured my work on Acting My Age, Tom Farber’s memoir on aging and mortality that we published as the winter 2020 issue of Manoa Journal. It has been my wonderful fortune to work on such books. Each writer teaches me, and in the course of my learning about the writing, I learn how to edit the work properly.

I should add that in my editing business, there have been times when I have failed to finish a project or please a client. These things happen, and it’s critical to analyze what occurred and why. I bring this up because it’s essential that people know they will have imperfect business lives, and a major part of continuing is learning how to deal with significant challenges or failures.

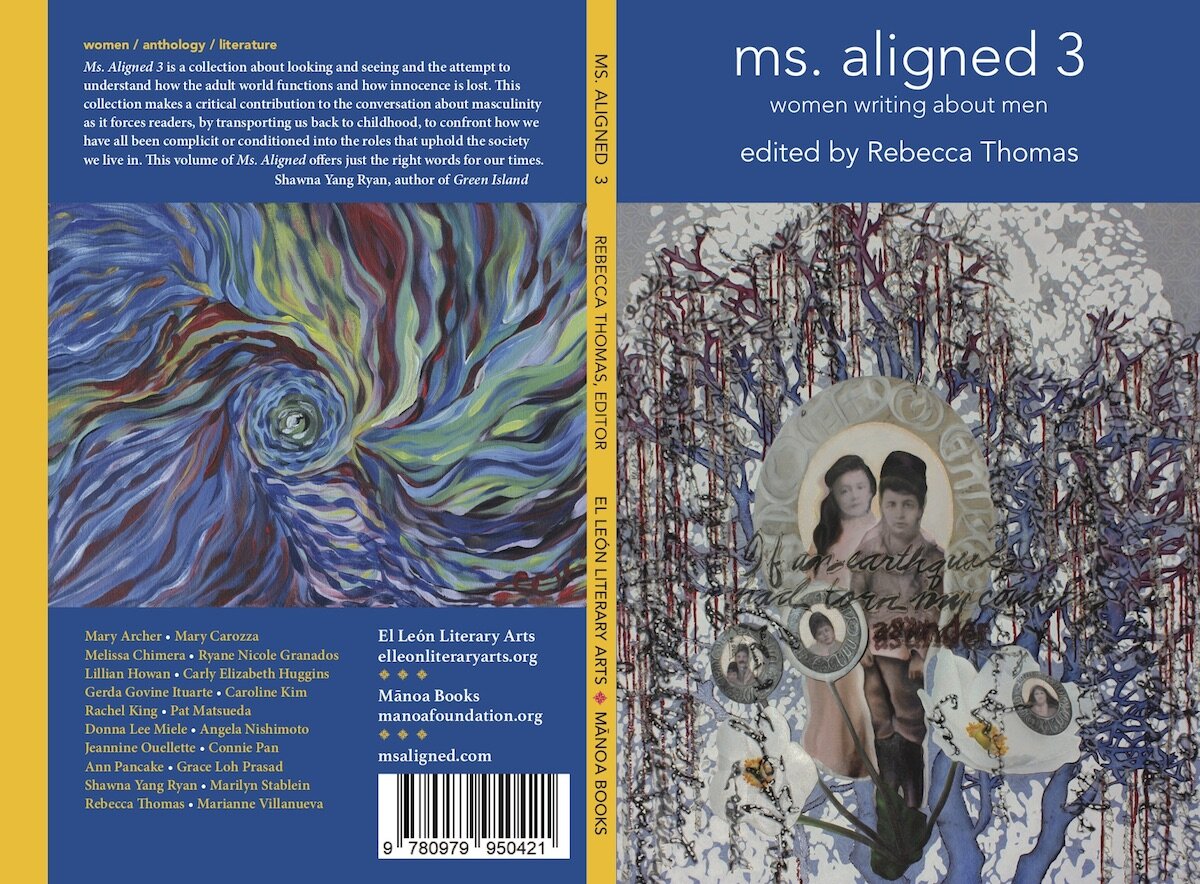

I asked the above questions for background, but I have curiosity about your founding of Aligned Press, from which you birthed Ms. Aligned, a series of three publications. I know you explained the reasons for your founding of this enterprise in 2016, and it's been a success. I recently re-read the three books, and feel that even though the first was published in 2016, the reasons for this literature existing, the situations we find ourselves living through, still occur. There seems to always be a need for explanations between people, male to female, female to male. That best-selling book Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, as simple and general as the concept seems, might have something to it. What do you think?

Yes, I certainly feel as you do: that the wisdom, insights, and observations gathered in the Ms. Aligned volumes have not lost their relevance.

Before you started Ms. Aligned, did you do any canvassing or talking about the mission of the series with people that have their fingers on the pulse of this phenomenon?

No, I didn’t. As I explain on the About page of our website,

The genesis for this project was a presentation at the 2014 annual conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs. The event attracted about a hundred people and was successful in generating both interest in the subject and thoughtful discussion.

It was the success of that event that inspired me to create the anthology. I’m happy that I did, as I also explain on the About page:

As far as we know, this is one of the few series devoted to writing by women about men. The contributors represent a diversity of cultures and ethnicities, and the stories they tell in their fiction, poetry, and nonfiction are complex—sometimes being about family, sometimes about society, and sometimes about country.

In the course I'm taking, Eng 713, guidance from Prof. Susan Schultz, is: find the puka, then fill it. What do you think about this technique in founding a publishing enterprise?

I think that’s possible in small press publishing. In the case of Manoa, we are part of an institution, the University of Hawai‘i, so our procedures are more regular or formal. Frank Stewart and Robert Shapard proposed Manoa in 1987 in response to a call for proposals from then UH president Albert Simone. The proposal was accepted partly because they said they would address the lack of an international journal focused on contemporary literary work from Asia, the Pacific, and the Americas and featuring new translations. In fall 1989, Manoa was launched with a double issue (spring and fall).

A complete list of our volumes is at our website.

For my small projects like Ms. Aligned or Vice-Versa, I’ll say it takes a great deal of commitment to produce a finished publication. Merely having a puka to begin with does not mean you’ll finish. You’ll come to rely on much of what you’ve learned and experienced to find your way to the end, and to get there you have to bring the force of your character.

When you receive submissions, how do you decide about what to accept, what to reject? I remember reading in Poets & Writers magazine, that many rejections occur because the work is not completed. I remember from your other journal, Vice-Versa ezine, that there were pieces on which you encouraged the writers to work on further. Do you trust your reason, your emotion, your gut? Please tell me about your vetting process.

I’ve reviewed many sets of guidelines for magazines and anthologies, and the same words tend be used. Editors are always seeking the best, the innovative, the surprising, the daring, the relevant, and so forth. These words glorify the publications, but they don’t help writers decide if they should submit their work. And that’s because they can’t.

What editors are looking for can only be narrowed down a bit but—unless they’re putting together a technical or scientific publication—not specified. I can say I chose a certain work because it was powerful, because it moved and impressed me, but does that help anyone understand what kind of writing I’m looking for? No, it doesn’t. The best way to get a sense of what editors want is to look at what they have already chosen: read their back issues, their anthologies, their series and see if you have similar pieces. Your work may ultimately be rejected, but generally, you will make better, more informed decisions.

I remember your delight at good work. I remember you said that you love publishing because you are always surprised. You never know what you'll get. Could you speak to this, please?

I don’t remember saying I am always surprised, though I might well have. What I do remember saying is that perfection can never be achieved, which drives us to try. When we publish the perfect book, we can quit. Until then, we will always be trying to perfect the design, editing, proofreading, and so forth.

You are rightfully happy and proud at the artistic successes of the Ms. Aligned series and Vice- Versa ezine. Is the quest for excellence enough of a motivator for you? From taking the class this interview is for, Eng 713, I see that people do art because they have to, they are driven toward making things beautiful. Over the years, I’ve come to see that you are ultimately an artist in pursuit of beauty. Could you speak about your personal philosophy behind your art?

I like to put disparate things together and think about the relationships that result—no doubt the result of what I was exposed to in high school and college; the art/art history courses I took; the experimental and avant-garde films I saw; and many trips to the Honolulu Museum of Art.

A good example of putting disparate things together is Illness as a Form of Existence, the latest issue of Vice-Versa, which features photographs by Jonathan Morse. Putting Jon’s photos on certain pages and imagining how readers might think about them in relation to the text was an interesting problem. If you look at Michelle Matthees’ poem “Restart,” for example, and think about the photo of Jon’s that appears beneath it, you’ll see correspondences between the two. A different kind of effect is produced by placing a photo of Jon’s in Matthew Goodman’s New York City “bunker diary”—one that causes you to react to the image differently and to ponder its placement.

The first Ms. Aligned cover caused some disagreement over its meaning or rather symbolism. I found the cover photo to be a beautiful, powerful statement about nascent masculine identity, but others saw it as a raw, aggressively sexual statement. The photographer, Kate Joyce, skillfully expressed the image’s beauties and subtleties in her artist’s statement—a piece I am very proud of having published.

Why do you enjoy publishing?

There are many reasons to go into publishing. Doing something because no one else has done it or simply because you believe it should be done. Putting in book form the writing of someone you admire and giving readers the chance to discover it. For some of us, these are goals worthy of effort and sacrifice.

Making a living has to be one of the least pragmatic reasons. If you are thinking of publishing as a second career or profits as a second income, I would discourage you from taking it up. You will be disappointed.

Publishing is also a good way for introverts to contribute to the vitality of their communities. We don’t have to perform or be in the public eye; we can do what we do in offices, behind doors, and feel we are engaged in good, valuable work. We get to spend all day reading, editing, and corresponding—things that introverts are good at. Plus that, we get to meet and socialize with other introverts.

Do you have a mission statement for Ms. Aligned?

Yes: “Ms. Aligned is a collection of writing by women about men: work written in a male voice or featuring a prominent male character. The series exists to discover and publish this writing.”

I remember that Ms. Aligned grew from a seed planted during a session at AWP in 2014. The first Ms. Aligned was published in 2016 as a POD. What’s involved in starting a small press?

The first Ms. Aligned was published as a downloadable PDF file for $4.99 at lulu.com. POD means print on demand, which produces a hard copy. I chose not to print the first edition because of the art it contained: I wanted readers to be able to enjoy the painting and photography in all their intense color and vivid detail.

When I created the entry at lulu.com for that edition, I created Aligned Press. It was therefore an entity called into being by publication requirements and had no basis in reality, which is to say that there is no such business in Hawai‘i. I think many people invent presses like this—e.g., South Point Press, created by Michael McPherson—when they cannot find houses at the time they want to publish.

You can usually tell if a book is not published by an established house. The marks that would normally appear on the cover, for example, are missing. Publishing houses perpetuate themselves through their line of books, so they make sure that readers and bookstores see their logo and are given other essential information about them.

I just looked up “small press” on Wikipedia and see that its definition is changing, in large part because technological advances allow more people to get involved in publishing, and these people innovate to suit their or their clients’ needs. Ms. Aligned occupies some part of the landscape defined in the Wikipedia entry, but I think of it as a series of projects rather than a small press.

How do you find what you want to publish?

For Ms. Aligned, we sent out email solicitations to people we knew, printed flyers and passed them out to strangers—most recently at the 2019 AWP conference in Portland—and made announcements on social media, first Facebook and then Twitter. Sheyene Heller was the coeditor of the first edition, and because of her connection to the Antioch creative writing program, we received submissions from some of its graduates.

Even with many good people helping, it takes a lot of energy to gather enough material for a book.

How do you turn down work you do not want to publish?

This is a sore point for me because I am very sympathetic to authors and hate to turn people down. Some people make it easy, of course, by being unpleasant, but most are polite, expectant, optimistic. Having been rejected often myself, I hate for them to be.

I can’t say that I am a good model for this kind of correspondence.

How did you raise money for your press?

The first edition of Ms. Aligned was funded in large part by a grant from the University of Hawaii’s SEED Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Access and Success (IDEAS) program. The second was funded by a smaller grant from SEED/IDEAS, and the third by a Kickstarter campaign.

At the beginning, it was mainly me writing grant applications. When we got to Ms. Aligned 3, I had a small team helping to raise funds. All the money we made for that edition went into the book. Money made after the book came out was used to pay off debts.

I want to emphasize, though, that we have been able to pay all our contributors. I feel it’s very important to pay women for their intellectual and artistic labor.

What do you do when you edit creative work? How does it affect your own writing?

There is definitely a symbiotic relationship between editing and writing. I am a more careful writer and more thoughtful editor as a result of doing both for so long.

I once described editing as going deep into a work, diving into the sentences, the words, and staying there. It is really another realm or dimension of being—absorption in a literary work—but there I’m also responding to the author’s choice of words, tone, characterization, use of time, and so forth.

Recently, I copyedited a translation from Chinese to English of a short story: the translator used the phrase “female scent,” which I changed to “womanly scent.” Why is there a difference? What does it say about the writer, about the narrator? These are things I think about and debate with myself.

How do you do design work? Do you sometimes find other people to do it for you?

I use standard design applications: QuarkXPress, which is what I started with, and InDesign. To create my covers, I use Photoshop. I would say I’m at the intermediate level in terms of design skills, but I try hard and can spend many hours working on just one thing. However, I do occasionally take things for granted. For example, having looked at proof pages three times, I can decide that a last look before it goes to the printer is not needed. I learned a good lesson about that recently.

Working on the books and magazine page of my website, I ended up putting several book covers in a gallery. The first image is the cover of my forthcoming chapbook, Bitter Angels. As I say on the homepage of my site, the chapbook cover consists of three pieces of art: a photo of the Statue of Liberty taken from behind the figure; a Copernican astronomical chart; and a photograph of the Milky Way. Combining these in Photoshop was a wonderful and exhausting process. When I finally had an image I was satisfied with, I put it in QuarkXPress and began adding the text. The textboxes became another graphic element when I added color and transparency to them. This whole process took many hours of experimentation over several days.

I would tell people who are curious about design to download a trial version of a popular application and devote a lot of time to experimenting with and learning it. There are also many tutorials on YouTube that you can watch to help you.

When is a book more than a book?

In working on my new poetry chapbook, Bitter Angels, I was faced with many decisions and ended up revisiting and changing some of them. As I was assembling the book, my sister, who was very ill, went into sharp decline and passed away. That affected my feelings about it. I came to see it as having its own mortality, and though its life might be brief, I wanted it to be intense and worth the struggle of being born.

It’s also true that every book is more than a book. At this point, I’ve worked on sixty volumes at my day job (managing editor at Manoa Journal), three editions of Ms. Aligned, and three of my own books—as well as a couple of ezines. Despite all that experience, I find that every publication teaches me something new—in fact, many new somethings.

How do you find and work with a printer?

Printers vary in so many ways, and as I found out with Ms. Aligned 3, the same printer can do different work at different times. We had the third edition printed by Kindle Desktop Publishing, and the proof copy we received was fine. However, the bulk copies were badly printed: the images were too dark, and there were many blank pages at the end. I then had lulu.com print it, and the quality was much better. With that printing, I also selected a glossy cover, which improved the color and detail of the cover images.

Cover paintings by Carly Elizabeth Huggins (left) and Melissa Chimera (right).

With my forthcoming chapbook, I tried to print via lulu.com and Kindle. My experience with Kindle was so disappointing—they gave me incorrect formatting instructions—that I stayed with Lulu. The book is printed on premium paper using premium color printing, which means that it will look and feel different from most poetry chapbooks. I chose these options because of the color that appears in the book, not wanting to compromise on the quality of the experience of reading and handling it.

Mistakes and disappointments with printers are sometimes unavoidable. One has to learn the hard way and chalk up the results to experience.

How do you distribute and market the books?

Of the three editions of Ms. Aligned, the third did best in terms of sales and distribution. This was mainly due to the crowd-funding campaign and purchases by contributors who wanted copies for friends and family.

Even though the series hasn’t been successful commercially, I regard it as an artistic success. Much of the writing we published was impressive, powerful, unique, and I am very proud of it. Each edition has its own character and presents a different facet of the effort by women writers to represent men.

How did you find your audience? How could you attempt to shape it?—if that’s what you’d like to do.

I’m not sure if you mean my own books or those I help publish. In the case of my own books, I find it hard to reach readers, though my website, someperfectfuture.com, tries to prepare them for the experience of reading my work. When a book of mine finds its way into the hands of someone who likes it, I am surprised and pleased. It’s like a salmon swimming upstream to find a resting place. It cannot do otherwise, and yet it is such a triumph to get there.

I think the thing to be is a good reader: someone who understands what a skillful and thoughtful writer is trying to do. I had that experience recently and was pleased—as was the author—that I was ready to receive the work.